Explore our collection of informative and educational blog posts to stay updated on the latest industry trends and expert advice.

The Value of Mistakes: Should It Matter How Long A Student Takes To Learn?

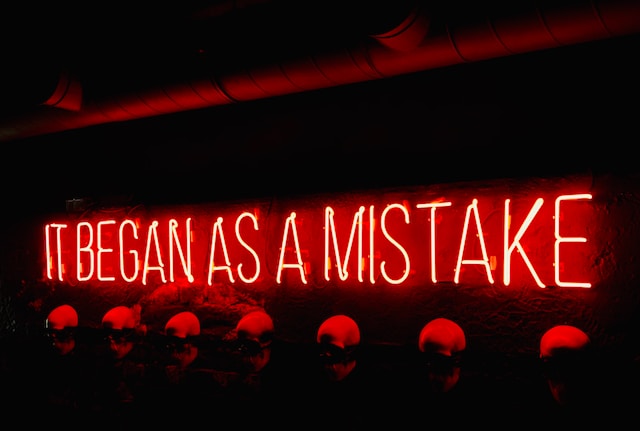

James Joyce affirms that geniuses not only accept mistakes as part of the learning process, but willingly seek them out as doors to self-discovery. In education, our perception of mistakes is important. It challenges conceptions of what defines success and failure.

The greatest mistake I ever made in my education was failing a physics course at Cornell. I opted to take an auto-tutorial class that did not require calculus because I was afraid to make math errors. Up until this point, I had never failed at anything. It was a turning point for me. I had to dispel prior notions of learning to succeed. I accepted that there would be many errors along the way. I relearned the basics I had previously memorized through difficult examples and repeated, detailed lab work.

If we see knowledge as just enough to “pass a course” then we miss the point of learning.

Changing the way we see errors and the time it takes to learn can help us produce better learning outcomes. It allows students to engage independently in the learning process.

Why are mistakes important to achieve engagement and learning?

- We live in an age where we are a bit afraid to let children fail. Generation Y had ‘helicopter’ parents who were super involved in their children’s upbringing. Support is a great thing. But over-involvement in a child’s life can stagnate growth. The New York Times ran a recent article that considers how allowing children to make their own mistakes naturally, helps them develop a stronger sense of self. Research on parenting suggests that children with responsive parents who balance high expectations while respecting a child’s sense of self fare better. Allowing age-appropriate mistakes can increase confidence and problem solving skills.

- Educators can fall into the same trap as parents. We want to be responsive, but not overbearing. The goal of education, after all, is to have students solve problems independently. Students should be able to take a generalization and apply it to different situations. Mistakes are the basis of application. They allow for experimentation.

- If we don’t allow students to fail in the classroom we are setting them up for failure in the real world. If we see knowledge as just enough to “pass a course” then we miss the point of learning. Sure, students might get the ‘right answers’ on an exam but know little about solving problems. This is essentially what happened to me in Physics. I memorized the textbook because I realized I was not very inclined towards left brain thinking. Had I allowed myself to make more mistakes in my past learning, I would have probably fared better in college Physics. When it came to college, my memorization didn’t help much-the gaps in knowledge produced a poor foundation for future success.

- Taking time to engage in mistakes actually allows students to move to a deeper level of understanding. We can argue that this type of in depth learning influences their entire life, rather than knowing “just enough” to pass a course. One may question why more teachers don’t incorporate this approach? Well, it is counterintuitive. Mistakes are costly in terms of time. And time is limited in classrooms. But if we see learning as a continuum based on the individual, rather than set principles we must achieve, it breaks down this reasoning.

- Every person will learn differently and perhaps focus on different parts of a topic. If we see learning this way, allowing mistakes seems more logical. For example, I just talked to my daughter’s first grade teacher about her reading skills. She is currently reading on the middle of the continuum-she may very well progress to level 2 or stay at her current level. Whatever her reading level is at the end of the year it is okay as long as she is challenged, because she has already mastered the basic skills of reading. There is no “set” level she must achieve each month. Learning is based on her individual progress. A continuum allows room for errors.

[ois skin=”In post”]

Why do we avoid mistakes in our current model?

- Our education system often punishes errors, rather than rewarding risk-taking. Schools were modeled in the Industrial Revolution to be efficient and reduce time spent on divergent thinking. After all, in a factory environment, divergent thinking might break down a process or the status quo. In today’s global technology-based economy, we often want students to do the opposite-to find a way of improving a process or a way of seeing things differently.

- Our grading system, on a scale of A-F follows with this approach of seeing failure and errors as a thing to be avoided. In some cases, perhaps failure is just that, a lack of understanding that needs to be corrected or lack of preparation. But mistakes on the way to mastery can be valuable learning opportunities. They solidify learning connections.

- Mistakes require a time investment. We can teach the entire textbook, but if students can not apply knowledge to solve problems it is meaningless. We may want to focus less time on covering the entire scope of knowledge, and rather focus on real mastery. As the saying goes, learning that is mile wide, inch deep is not very useful. A student can go back and fill in the different topics if there understanding of a topic is deep enough to solve problems. Application of knowledge is more important than acquiring additional superficial knowledge-which is easy in today’s day and age with technology.

- Our current standards focus on topics that should be covered, in addition to skills. If we only focused on skills, teachers would have more time to go deeper into subject areas and allow students enough time to achieve mastery. Sometimes, teachers are racing against the calendar to make sure all required topics are covered by the end of the year. Less specific standards on a continuum might be more beneficial, rather than rigid requirements.

-

We define success as limiting the times we fail. Instead of focusing on complexity and mastery, we measure success as the number of times we avoiding making mistakes. On many exams, we are choosing the correct answer, rather than demonstrating we can solve a complex problem.

We try to reduce the time spend on trial and error. We don’t think students will clearly understand a topic if they make errors. A better way would be to consider what errors students are making-and focus on how a student applies knowledge. Exams can focus on building information, rather than regurgitating it.

- We focus more on lecturing and providing a foundation for knowledge. Lecturing can afford students with a basic understanding of a field, but when solving problems trial and error is necessary. For example, most homework is a problem set, or application of a lecture.

- At times as educators we try to avoid assigning problems that are too challenging. We may not allow opportunities for blunders to occur. We are afraid that making too many mistakes might confuse students. But when we lose sight of mistakes, we may be missing exceptional learning opportunities.

- Learning is teacher directed, rather than student-led. In the old model, learning often focuses on listening to the teacher lecture and then applying knowledge to specific situations. We might want to consider reversing the order of traditional learning: presenting a problem first and then letting students learn how to solve it. This type of reversed learning scenario allows opportunities for growth through trial and error.

Our current model often tries to curtail errors. We limit the time students spend in class figuring things out on their own.

Mistakes can be a very powerful learning tool. How we view mistakes can transform our classroom model. Our current model often tries to curtail errors. We limit the time students spend in class figuring things out on their own. We see learning time as a limited resource, rather than approaching learning as a continuum individual to each learner. We set standards that are the same across the board and allow little room for mistakes.

PART 2: Turning Mistakes Into Learning Opportunities

Today, if you asked me about my most memorable learning failures, I will tell you I am glad they happened. My errors have made me a better teacher and learner. I can now relate to students who have a difficult time understanding a concept. The failures themselves may not have been my strongest point, but what I learned from them was invaluable. Mistakes can be excellent learning opportunities.

It may seem contradictory: to create situations where students will make mistakes purposefully. We might allow extra time for class problem solving or focus on more challenging examples. Errors often result in increased knowledge. Controlling where and how these errors occur is an option. Frustration can result if no resolution and feedback are given after errors are made. A positive classroom environment that encourages students may also provide a good groundwork for allowing this type of learning.

How can we use learning errors to our advantage?

- Instead of discouraging errors, educators should find ways to support individual learning processes. Carol Dweck, a psychologist at Standford studies motivation and found that rather than praising intelligence, educators should focus on encouraging students to think of their mind as flexible and support individual responsibility. Similarly, Jonah Lehrer, in “How we decide” talks about how educators suppress problem solving and may make students feel that mistakes are a sign of lesser intelligence. Lehrer suggests relying less on praise and allowing time for students to develop skills on their own. “. . . Instead of praising kids for trying hard, teachers typically praise them for their innate intelligence. . . . This type of encouragement actually backfires, since it leads students to see mistakes as signs of stupidity and not as the building blocks of knowledge.”-Lehrer

- Accept mistakes as part of the learning process. Half the battle is realizing that errors can be used as learning tools. The other half is learning to use them correctly. Mistakes can work to our advantage. Some students resort to memorization, rather than risk making errors. But something is lost if education does not allow students time to try things on their own. Many teachers steer away from this model because mistakes take away valuable instructional time. But some new proponents argue there may be something wrong with this model. Perhaps we must reconsider why we aren’t letting students make their own mistakes.

- Achieving mastery should be the purpose of education. Professionals are essentially experts who after years of study have learned specifics in a field. But the process of learning a concept is just as important as the concept itself. Why? Mastery produces learning that is meaningful.

-

Use mistakes as part of a discovery process that engages students. Allowing time for individual exploration will create opportunities where failures may occur, but they can be used as a tool. In a recent talk, Noam Chomsky discussed how education should allow students to search, inquire and pursue topics that engage them. Chomsky believes that education should allow students to discover on their own. Education should prepare students to learn on their own in an open-ended way.

- The Khan Academy is a great example of this. Their model focuses on students experimenting to achieve mastery. The Khan Academy is essentially a series of educational videos in math and other subjects. Their aim is to have a student be an expert before moving on to another subject. Using interactive exercises, teachers can gauge student understanding.

- Focus on self-paced learning strategies whenever possible. Media can be used to incorporate self-paced learning in the classroom, where students complete lectures at home, and “homework” examples in school. This saves classroom time and switches the focus of learning to problem solving. Students learn general information at home and practice examples in class. Allowing students to make errors in the classroom, rather than at home is beneficial. At home, there is no teacher or at times, support may be absent to guide students who may give up and not ask a teacher the next day. Salman Khan compares achieving mastery through experimentation to learning to ride a bike. The gaps must be bridged before students can move on to the next skill. You cannot ride a bike without achieving balance first.

- Use technology can turn errors into a teachable moment. Some teachers use student examples on the overhead or power point to show divergent thinking and how students might approach a problem differently. Actually showing mistakes during class (with their names to avoid embarrassment), can make students realize that they are an acceptable part of the learning process. Seeing another student’s mistakes can also help bridge learning connections.

- Use immediate feedback to reduce frustration. Bill Gates pointed out that the Khan academy relies on “motivation and feedback” of a learning process. Immediate feedback from mistakes in learning can actually be a powerful learning motivator. The teacher can serve as a resource that helps students find answers on their own.

- Accept that learning is a messy process. When attempting one of his inventions, Thomas Edison once said, “I haven’t failed; I have just found 10,000 ways that didn’t work.” If we want to encourage our students to achieve their ultimate best, we must acknowledge that learning is non-linear. Each learner will have preferences and inclinations. No two students are the same. By accepting this, we allow room for individual differences. By allowing students to make errors, they can better assimilate information to their needs and learning styles.

- Rather than resorting to memorization, allow students time to practice in class. They may discover that their weaknesses are just different ways of approaching a subject. Rather than a weakness, their errors can be ways to realize that they are just seeing things differently. They are part of a greater learning process that is individual to each learner.

- See learners as apprentices. An apprenticeship is a good way to understand how this model works. An apprentice works for years under a Master until he is ready to complete the task on his own. He is allowed to make mistakes, and even encouraged to do so. After learning the basic skills from the master, an apprentice is often required to design a complex project on their own that showcases their unique skills. Errors are considered part of the process of being an novice. The trainee eventually develops his own style and point of view. After many trials, the apprentice becomes the master.

As James Joyce suggests in Ulysses, a true genius sees all learning as an opportunity to improve and discover. Errors are taken at will. In making mistakes, we can reach new heights and finds our true genius.

While one person hesitates because he feels inferior, the other is busy making mistakes and becoming superior. – Henry C. Link