Explore our collection of informative and educational blog posts to stay updated on the latest industry trends and expert advice.

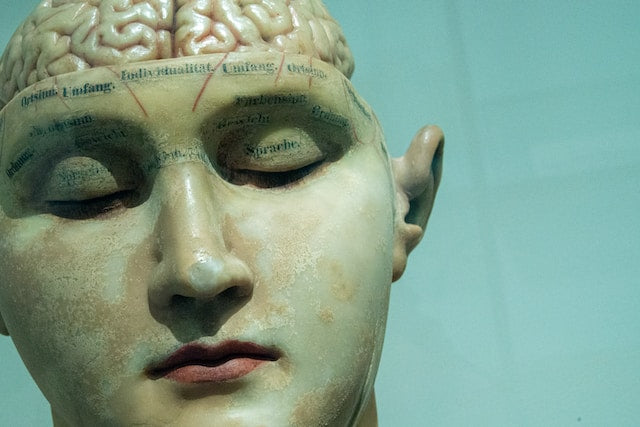

5 New Ways to Improve Your Memory

We’ve all heard about memory strategies like spaced repetition and retrieval practice, but what else is there? Actually, neuroscientists are discovering some pretty exciting things about the way memory works, and as always, we’re here to share their research with you. Here are five ways to improve your memory based on the latest findings:

1. Identify the “functional meaning” of the information.

If you know why you want to learn something, and can imagine using the information for that purpose, it will be much easier not only to learn it but to recall it when you need to. The “functional meaning” of information can range from using it at work to making conversation at a dinner party. If you can imagine the setting in which you plan to use it, you’ll recall it better once you’re in that context because you’ve primed your brain to think about it then.

“What enters into a memory representation (what is encoded) is determined largely by the perceived functional meaning of an item, and this in turn determines which retrieval cues will be most effective for memory retrieval,” say researchers at the University of Oregon and Arizona State University.

2. Match encoding and retrieval cues.

“Forgetting is caused in large part by a change between the context of acquisition and the context of retrieval,” writes neurobiologist John H. Byrne in his reference book on Learning and Memory.

If you think about it, a huge part of casual conversation depends on how good your retrieval cues are: When a friend shares a story on a certain topic, and you want to reciprocate with your own, you have to be able to pull the appropriate information out of long-term memory based on the cues your friend is supplying with her own story. But that only happens if you encoded the memory in a way that pairs up with the present context. The same is true for remembering facts, as you’ve probably heard when it comes to “state dependent learning.”

3. Categorize material before you learn it.

Research on visual and auditory perception suggests that working memory relies on synchronicity between three brain regions: the prefrontal cortex, frontal eye fields, and lateral interparietal lobe. When we have more than four or five visual stimuli to pay attention to, the feedback loop between these regions begins to break down. Why, exactly?

Neuroscientists believe that the brain depends heavily on something called “predictive coding” to function normally. In this case, when the prefrontal cortex reaches its full capacity to “model,” or predict, what information it will receive from the other two regions, working memory stops… well… working.

“When the quantity of items placed in working memory gets too large, the number of possible predictions for those items cannot easily be encoded into the feedback signal. As a result, the feedback fails and the overloaded working memory system collapses.”

Karl Friston, a neuroscientist at University College London, explains it this way: “As you are reading this sentence, you will have expectations about the current word, phrase and sentence. Having a representation or expectation about the current sentence means you have an implicit representation of the past and future.”

Spending some time thinking about the type of information you encounter on a daily basis can help you retain more of it by setting predictive categories for it to fall into.

4. Assume you will forget it.

Most of us walk around under the false assumption that we’ll remember new information simply because we’ve encountered it. Closer to the truth would be the assumption that we’ll forget it.

Researchers have found that dopamine is involved not only in remembering but in forgetting as well. In fact, some neuroscientists now believe that forgetting may be our brain’s default function when it comes to processing new information.

When we receive new information, we create an engram (physical trace of memory) that immediately starts to deteriorate unless we strengthen it by recalling it.

This is necessary for brain health, but it also means we need to pay special attention to the information we want to stick with us, and work to remember it.

5. Brain-dump your worries before you learn.

Research has shown that people who can quiet their Default Mode Network have higher working memory capacity. The Default Mode Network is associated with mind wandering, especially in terms of one’s “narrative self.” It makes sense: when we’re going through a breakup, for example, we often can’t think about the task at hand; and if we can, the unpleasant experience is still in the back of our heads, taking up cognitive space that would otherwise be free for learning new material. The DMN is like a net in the back of your mind that catches this information and doesn’t let it pass through into long-term memory.

One way to solve this is to do some journaling each morning to clear your head. Or, if you prefer talking it out, do a brain dump with a friend. Either way, be aware of the fact that your concerns and daydreams may be taking up space in your brain whether you feel distracted or not.